Day 3. A Pedigree

DAY 3 - A Pedigree

The death of Elizabeth Gall was an opportunity: Henry shed no tears. She had been the family matriarch over a quickly diminishing realm as nephews and nieces escaped her clutches by leaving the island. She and her sister had been single minded in buying back portions of Old Stingo’s estate which their brother had lost to the local moneylenders after the Great Storm. Plot by plot they had bought portions as they came on the market and they could afford them. Prices of land had plummeted after that great hurricane - many small plantations had been wrecked and then abandoned by their owners who sought their fortunes elsewhere.

The young Henry Beckles Gall had listened to his father’s interminable stories of the great fortune the Gall family had once had and rightfully should have been passed down from father to son. Aunt Elizabeth had no children of her own: so when she had instructed her nephew to send his two young sons to her to be educated properly in Barbados he had supposed that his aunt had relented in her feud with him over the slave John. The intention that the boys should leave Demerara was announced in the Essequebo & Demerary Gazette on 1st June 1816 and so it was that they landed in Barbados in the aftermath of the Bussa slave rebellion.

The boys looked into the eyes that stared back at them blankly. The bodies of the rebellious slaves swung in the sea breeze. William saw disloyal negroes. Henry saw the scars of old whippings; the open wounds which revealed under the black skin the same pink flesh as he had. William opined that they had to be taught a lesson if the population was to be kept safe. His younger brother just shuddered. “This is what happens when people in England interfere with our affairs. They have no idea what it is like here. The hardships we have to endure so that they can have sugar on their plates”. Henry kept his thoughts to himself. If it was true that the abolition of the slave trade would be followed by their emancipation then why had the slaves rebelled? And why had the Governor’s reaction been so harsh?

Elizabeth had quickly picked up on the differences between her two nephews. William would be trained to take over the running of her plantations. Henry Beckles should learn the theory and practice of accountancy. And so it was until Henry had decided to try his hand as a merchant like is father.

* * * * *

William and Henry were nothing alike; but they shared the same ambition - to secure Elizabeth’s fortunes for themselves. William argued that their great aunts, Elizabeth and Mary, had worked hard to recreate Old Stingo’s plantation and they would have wanted it to be kept in operation as a source of income. Henry was not so sanguine. It had brought on the ruin of both Old Stingo and their grandfather.

“ There was something wrong about the place, something evil.”

“Superstitious tosh. You are worse than the old negro women.”

But Henry’s arguments were more practical

“There is not a single year when Gall’s Retreat has earned enough to pay your salary. You have sold some of your best slaves to pay your way. The price of sugar has plummeted. The vegetables you plant are hardly fit to eat even by your slaves. Are you going to go back to planting Tobacco or cotton or indigo? I think not. The plantation will be your ruin and there will be nothing left from Elizabeth’s will if we don’t sell soon. We have to pay out £725 to other legatees before we can get our hands on our shares.”

“But that is the whole point, dear Henry. If we keep the estate intact then there is no cash to pay out these bequeathals. And there is no-one to gainsay that we are acting in the common good of all the family under this will.”

The whole of Elizabeth’s estate had been left to James Robinson Cook as trustee. There were some generous bequeathals to be paid out before the rest of the estate was to be divided equally between the two boys and their three aunts Polly Benjamin, Peggy Gall and Liza Barrell. Peggy had died at sea with Polly’s husband and the two sisters were now out of the way living in Connecticut. James Robinson Cook was now dead. William and Henry were the only two of the five main legatees still on the island. The other bequeathals were to old women friends of Elizabeth who may not have realised there was money due to them - and the boys did not know whether they were still alive. £725 plus £300 to James Robinson Cook “for his own use”. £1025 had been the sum that their grandfather had owed when he died in the debtors’ prison in Bridgetown. Elizabeth was having a laugh at them from her grave.

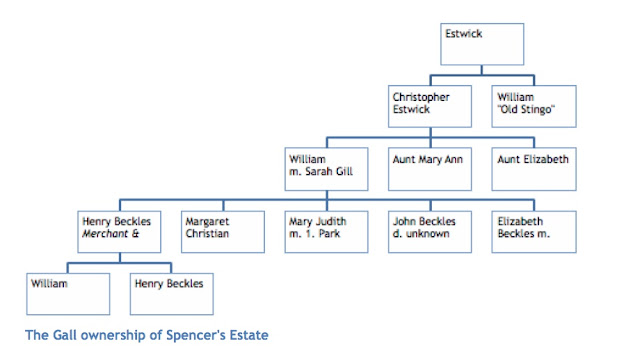

There were rich pickings in May 1831. William saw advantage in delay - keeping the estate together. Henry saw advantage in selling out as soon as possible. One way or another they were agreed that they should claim the administration of the estate and argue about liquidizing the assets later. And so it was that the two brothers faced the Provost Marshall one hot afternoon in Bridgetown, Barbados and proffered the family Pedigree - set out in Henry’s copperplate handwriting which showed the official that they were, with their two surviving aunts, the sole surviving descendants of Elizabeth Gall.

Comments

Post a Comment